Obama Kenya trip more than just symbolic

Barack Obama may not get quite the rapturous welcome he did when he visited Kenya as a senator back in 2006, but his presence in his ancestral home is something of a coup for the Kenyan leadership, and he is expected to be warmly received.

The country has never had a sitting US president visit before, and understandably there’s a sense of enormous pride.

For the Americans, this is a golden opportunity to gain some leverage at a time when security threats posed by the Somali Islamist group al-Shabab bind both nations together.

From a personal standpoint, it’s a time for Mr Obama to build on his legacy here.

Without doubt, President Obama is trying to “recalibrate” the relationship between America and Kenya after some difficult diplomatic times.

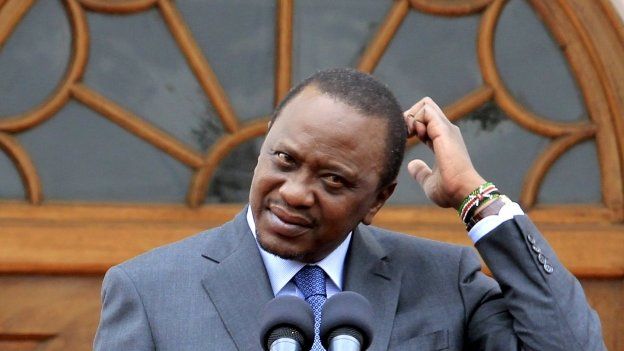

Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta was up until recently indicted by the International Criminal Court (ICC) in The Hague for charges relating to a previous election.

That proved problematic for the US president, whose envoy warned Mr Kenyatta as he campaigned for the presidency back in 2013 that there would be “consequences” as a result of not trying to clear his name first.

Months later, Mr Obama delivered a significant snub to Kenya, bypassing the country altogether during his last African tour.

It was deeply felt here in Kenya. Ordinary Kenyans saw it as a personal affront, and the diplomatic sidestepping was met with a ratcheting up of anti-Western sentiment by the Kenyan leadership.

But the charges against Mr Kenyatta have now been dropped, in part due to the Kenyan government’s apparent “lack of co-operation” with the court.

It would appear that all is forgiven, and the words of warmth have returned.

Mr Kenyatta confirmed as much in a pre-visit briefing, when he made it clear his US guest was expected to meet his deputy, William Ruto, who still has charges from the ICC hanging over his head.

The imperative of working to defeat terrorism would appear to trump matters of international justice. In diplomatic speak, they call it “essential contact”.

Mr Kenyatta said “the fight against terror will be central” to bilateral talks, and pointed out that Kenya had “been working in very close collaboration with American agencies” and was expecting to “strengthen” ties during the visit.

That policy of appeasement is certainly something many security watchers in Kenya have sensed.

Peter Alling’o, from the Institute of Security in Nairobi, believes the US is seeking to restore close relations with Kenya, in order to gain a stronger foothold in the region’s security apparatus in the face of al-Shabab attacks.

It may also help to ensure a few more contracts go America’s way.

China and its eastern neighbours now player a bigger role in Kenya – not only in building roads and railways but also in the important area of defence procurement.

Military vehicles and some weapons have an increasingly Eastern flavour here.

Obama’s 2006 Kenya visit:

Barack Obama visited Kenya as a senator in 2006. His father was a goat-herder-turned-economist from western Kenya.

Included in his itinerary were a visit to Wajir, a rural area in north-eastern Kenya hit by a severe drought, and a tour of Kibera, a slum area housing at least 600,000 people.

He also took an HIV/Aids test at Kisumu, which had one of Kenya’s highest rates of HIV prevalence, to encourage local people to do the same.

During the trip, he was asked if he planned to run for president. He said: “The day after my election to the United States Senate, somebody asked me am I running in 2008. I said at that time, ‘No.’

“And nothing, so far, has changed my mind.”

So what will the Americans be hoping to get out of bilateral talks on security, and what about the Kenyans?

Kenya will be able to continue to count on the Americans for “closer military support, training and procurement of hardware”, says Mr Alling’o.

In return, by offering a growing sense of “confidence and trust” in the Kenyan security forces, he believes the American objective is to “penetrate the Kenyan intelligence services more deeply”.

It is a delicate relationship and one President Obama will have to navigate carefully.

The Americans have some misgivings about what many see as the heavy-handed approach applied by Kenyan security forces to the country’s Somali community.

Talk of building walls along the border, and closing the sprawling Dadaab refugee camp, which is home to thousands of Somali refugees, has not impressed the US leadership, as was made clear during Secretary of State John Kerry’s recent visit.

But President Obama’s uncle, Said Obama, who has visited him several times at the White House, told me his nephew’s influence across Africa could be far more widespread once he had cast off the shackles and constraints of the presidential office.

Kenya is a proud nation and one that has proven resilient in the face of terrorist attacks, most notably those at the Westgate shopping centre and the assault on Garissa University earlier this year.

But the country’s leaders are likely to respond better to gentle persuasion rather than public humiliation when it comes to policy matters.

And Mr Obama may be perfectly placed to deliver that.